Deposition of Wesley Fuller in the Preliminary Hearing in the Earp-Holliday Case

The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, one of the most famous shootouts in the American Old West, took place on October 26, 1881, in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. The confrontation involved lawmen Virgil, Wyatt, and Morgan Earp, along with Doc Holliday, against the outlaw Cochise County Cowboys, including Ike and Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury, and Frank McLaury. Tensions had been building for months between the Earps and the Cowboys, stemming from political differences, law enforcement disputes, and personal grudges. The actual gunfight lasted only about 30 seconds, with the Earps and Holliday emerging victorious, killing Tom and Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton.

Although the gunfight was relatively brief and took place in a small alley near the O.K. Corral, its impact on American folklore and the mythos of the Wild West has been significant. The shootout was later romanticized in literature, film, and popular culture, often portraying the Earps and Holliday as heroic figures standing up against lawlessness. However, the events leading up to and following the gunfight were complex, involving legal battles, public opinion, and ongoing violence, reflecting the broader conflicts of power and law in the tumultuous frontier society.

Testimony

On this seventh day of November, 1881, on the hearing of the above entitled cause of the examination of Wyatt Earp and J. H. Holliday; Wesley Fuller, a witness of lawful age, being produced and sworn, says as follows:

Deposition of Wesley Fuller, a gambler, of Tombstone. He states he saw the difficulty between the Earps and Holliday on one side and the McLaury brothers and the Clantons on the other, on Fremont, near the comer of Third Street. He was right back of Fly’s Gallery in the alley when the shooting began. He says he saw the Earp party, armed, at Fourth and Allen and that he was on his way to warn Billy Clanton to get out of town. He saw Billy, Frank McLaury and he thinks Behan, but did not gel to speak with Billy, as just then the Earps hove into view, and he heard them say, “Throw up your hands!” Billy Clanton threw up his hands and said, “Don’t shoot me! I don’t want to fight!” and at the same time the shooting commenced. At this time, he had not seen Tom McLaury nor Ike Clanton.

He says the Earp party fired the first shots. Two were fired right away, they were fired almost together. They commenced firing then very rapidly and fired 20 or 30 shots. Both sides were firing. Five or six shots were fired by the Earp party before the other party fired. Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury were the only two I saw fire of the Clanton party. As the first shots were fired by the Earp party, Billy Clanton had his hands up. [Shows the position as he stood raising his hands up to the line of his head.] Frank McLaury was standing, holding his horse when the firing commenced. He was not doing anything that I could see. He had no weapon that I saw on him. I saw his hands and he had nothing in them. If there had been, I would have seen it. I think the first two shots were aimed at Billy Clanton. I saw that he was hit. He threw his hands on his belly and wheeled around. I did not see any effect on anybody else at that time. Frank McLaury drew a weapon and was firing during [illegible]. When he drew his weapon, he was on Fremont Street, a little past the middle of the Street. [Shows on diagram.] Further talk as to relative positions. Then he says, on questions, that seven or eight shots had been fired by the Earp party before he saw Frank McLaury draw his pistol. He tells of the space between Fly’s and other building, and says he saw Tom McLaury there. He did not see Tom again until they brought him into the building. He does not know where Ike went after seeing him pass through this building. He says Tom was staggering, as though he was hurt. He did not see any arms or even a cartridge belt on Tom after he had been brought into the building where he died. He never saw Ike with any arms at the scene of the battle. He tells of seeing Billy rolling around on the ground in agony. He helped take him into the building. He says Billy said to him, “Look and see where I am shot.” He looked. He tells of wound in belly and other near left nipple. He says he told Billy he could not live. Billy said, “Get a doctor and give me something to put me to sleep.” He says this is all he recollects; that he did not leave until Billy died.

He says he saw Billy shooting during the fight, a pistol; that he was then in a crouching position, sliding down against the comer of the house. He had drawn his pistol with his left hand. He says six or seven shots had been fired by the Earps before Billy drew his pistol. He says Billy was shot in the right wrist. When he saw Frank in the middle of the street, drawing his pistol he was staggering then appeared to be wounded, acted dizzy. He says Billy and Frank each had a horse there and he thinks each had a rifle strapped on in a scabbard. He is sure this was true of Frank’s horse. More talk about the rifle on Frank’s horse. He tells of Frank leaving the horse in about the middle of the street and staggering up the street. He says previously it seemed as if Frank was trying to get the rifle out of the scabbard, but the horse kept jumping away from [him]; “He was fooling with the horse.” He says probably seven or eight shots had been fired by the Earp party, “probably more,” before Frank commenced trying to get the rifle.

CROSS EXAMINATION

He states he was on Allen Street between Third and Fourth Streets, on the north side, just below the O.K. Corral, when he first saw Billy Clanton, Frank McLaury and Johnny Behan on Fremont. He relates of seeing Holliday put a six-shooter in his coat pocket at Fourth and Allen. Saw one in Morgan Earp’s pocket, on the right side. Wyatt had one pushed down in his pants on the right side a little. I was standing on the comer of Fourth and Allen Streets, I mean not far from them, about ten or twelve feet. I do not recollect what kind of a coat Wyatt Earp had on-at times the pistol was under his coat. I do not recollect whether Wyatt Earp had on an overcoat or not. When I saw the pistol, his coat was not buttoned. Virgil Earp had a shotgun.

He says he went right down Allen Street after seeing the Earps on the comer of Fourth and Allen, and “walked along not very fast. I stopped, probably four or five seconds and spoke a few words as I was going to this vacant space; I spoke to Mattie Webb. It was at the rear of her house that I spoke to her.,,3 He says he was not there when the first shot was fired. He shows on diagram how he went. He says he stayed in the alley but moved around during the shooting, “as bullets were flying around there.” He says he kept stepping backwards, but kept his face towards Fremont and the shooting. He locates the position of the various combatants on the diagram.

He goes on to say he thinks Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday fired the first two shots, but can’t tell which fired first. He says they were fired at Billy Clanton. He saw them shoot. He reiterates this. He denies he was excited. He denies he had been drinking during the day. On question says it was about 3:00 A.M. when he went to bed, and got up between 11 and 12, “I should judge.”

He admits he had been drinking the day or evening before the fight, considerable; indicates it was over a period of several days. He denies he had a fit of delirium tremens. He describes the character of the wound on Billy Clanton’s wrist by pointing to Mr. Fitch’s wrist, a point about three inches from the palm of the hand and says, “I think it was about there. I don’t know whether it was on the inside or outside of the arm.” He doesn’t know if it was on both sides, or deep, or shallow, and did not see any bullet in the hole, and doesn’t know the extent of the wound. He doesn’t believe Frank fired before he became separated from his horse. He is sure he saw Ike Clanton pass through the vacant space between Fly’s buildings and that Tom McLaury also staggered into the same area. He admits he knows William Allen, but doesn’t know if he is one of those who brought Tom McLaury into the house-“The house on the comer of Third and Fremont, the second house below Fly’s Gallery.” He reiterated that Billy was rolling around on the ground, and doesn’t know what became of his horse. He says Billy and his horse became separated immediately after the fight began and he did not see the horse again. He can’t place the horses on the diagram.

(Q) What are your feelings toward the defendant Holliday?

(A) We have always been good friends, and are so now.

(Q) Did you not, on the fifth day of November, 1881, about 5 o’clock in the afternoon, in front of the Oriental Saloon in Tombstone, say to or in the presence of Wyatt Earp, that you knew nothing in your testimony that would hurt the Earps, but that you intended to cinch Holliday, or words of like import or effect?

(A) I told Wyatt Earp then that I thought Holliday was the cause of the fight, I don’t say positively I might have used words, “I mean to cinch Holliday,” but I don’t think I did.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION

(Q) At the time you referred to, that you had the conversation with Wyatt Earp in the last interrogation, who was present, if anyone?

(A) There were parties there, but I don’t remember who they were.

(Q) Who were you talking to?

(A) Wyatt Earp.

[Signed] Wesley Fuller

References

The Tombstone Epitaph

The Tombstone Epitaph is a historic newspaper in the American West, closely tied to the lore of the Wild West and the famous town of Tombstone, Arizona. It was founded on May 1, 1880, by John Clum, a former Indian agent and the first mayor of Tombstone. The newspaper played a significant role in documenting the events of one of the most storied periods in American history.

Founding and Early History

John Clum founded the Tombstone Epitaph during a time when Tombstone was booming due to the discovery of silver in the nearby mountains. The town quickly grew into one of the largest and most notorious in the West, attracting miners, gamblers, outlaws, and lawmen alike. Clum, a staunch Republican and supporter of law and order, used the paper to promote his views and to support the efforts of the Earps, who were the town’s law enforcement at the time.

The newspaper’s name, “Epitaph,” was reportedly chosen by Clum as a nod to the violent and often deadly nature of life in Tombstone. He believed that the paper would serve as the “epitaph” for many of the stories and lives that would pass through the town. The Epitaph became known for its bold headlines, sensational stories, and fierce editorials.

The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

One of the most famous events covered by the Tombstone Epitaph was the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881. The shootout between the Earp brothers—Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan—and Doc Holliday on one side, and the Clanton and McLaury brothers on the other, was a pivotal moment in Tombstone’s history. The newspaper provided a detailed account of the event, and its coverage helped shape the public’s perception of the Earps as lawmen battling against lawlessness.

Decline and Revival

As Tombstone’s silver mines began to decline in the late 1880s, the town’s population dwindled, and the Tombstone Epitaph faced financial difficulties. The paper struggled to survive but managed to continue publishing, albeit with less frequency. Over the years, the Epitaph shifted from being a daily to a weekly, and eventually to a monthly publication.

In the 20th century, the Tombstone Epitaph experienced a revival as interest in the Old West and its colorful history grew. The newspaper became a cherished piece of Americana, and its archives were preserved as valuable historical records. In the 1960s, the paper was revived as a historical publication, focusing on the history of Tombstone and the American West. It continues to be published today, both as a historical monthly and as a tourist newspaper, providing visitors with stories and insights into the town’s storied past.

Legacy

The Tombstone Epitaph remains one of the most iconic newspapers of the American West. Its coverage of the events in Tombstone, particularly during the 1880s, has made it a key source for historians and enthusiasts of the Wild West. The newspaper not only documented the events of a bygone era but also helped shape the legends that continue to captivate people today.

Tombstone Epitaph Headlines

The Tombstone Epitaph – March 27, 1882On March 27, 1882, The newspaper the Tombstone Epitaph announced the murder of Frank Stilwell in Tucson Arizona. Frank Stilwell was an outlaw and a… |

The Tombstone Epitaph, March 20, 1882The Tombstone Epitaph, March 20, 1882 reports of the murder of Tombstone Resident Morgan Earp while playing pool in Tombstone, Arizona. This event followed the… |

The Tombstone Epitaph, October 27, 1881The following is the original transcript of The Tombstone Epitaph published on October 27, 1881 on the infamous gun fight at the O K Corral… |

Camp Osito Road – 2N17

Camp Osito Road is a back country 4×4 trail which connects Knickerbocker Road to Skyline Drive in Big Bear, California. The seldom travelled road is an access route to a local Girl Scout Camp.

Route 2N17 branches from the Knickerbocker trail about two miles from either end and wanders towards the west by Camp Osito. From there, the route continues through the heart of the San Bernardino Mountains until it intersects with Skyline Drive. This is at best an intermediate trail and offers views of Big Bear Lake and the surrounding forests and manzanita groves.

Big Bear Mountains, nestled in the heart of Southern California, offer a breathtaking escape into nature’s splendor. With a majestic backdrop of towering pines and rugged terrain, this mountainous haven beckons outdoor enthusiasts and adventure seekers alike. The towering peaks, including San Gorgonio Mountain, provide year-round recreational opportunities, from exhilarating ski slopes in the winter to invigorating hiking trails during warmer months.

Due to the proximity to Big Bear, it is quite common for this route to be used by hikers, bickers, quad riders and 4x4s alike, so keep an eye out for traffic.

Trail Summary

| Name | Camp Osito Road |

| Location | Big Bear, San Bernardino, California |

| Latitude, Longitude | 34.2243, -116.9378 |

| Elevation | 7,500 feet |

| Distance | 1.8 Miles |

| Elevation Gain | 352 feet |

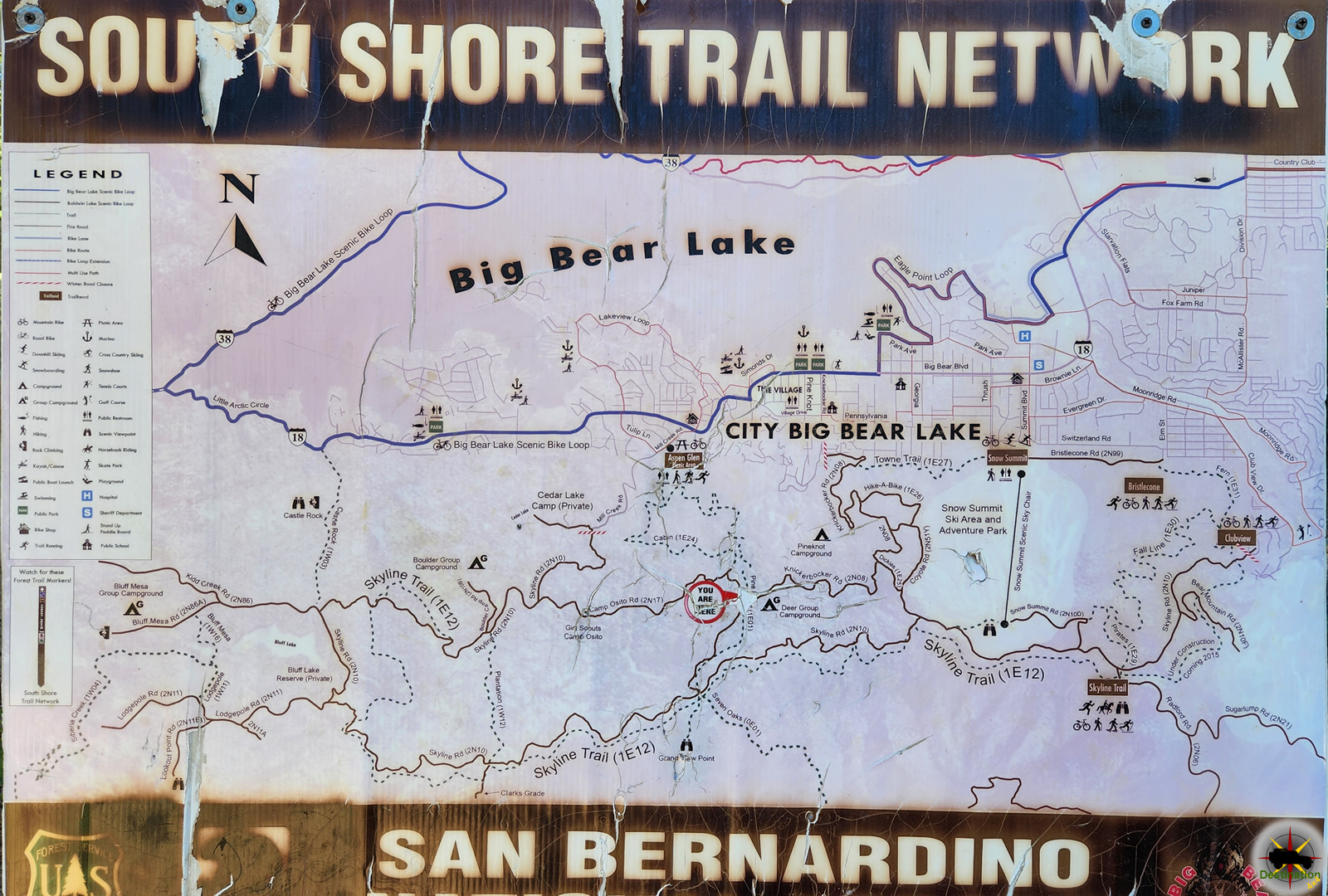

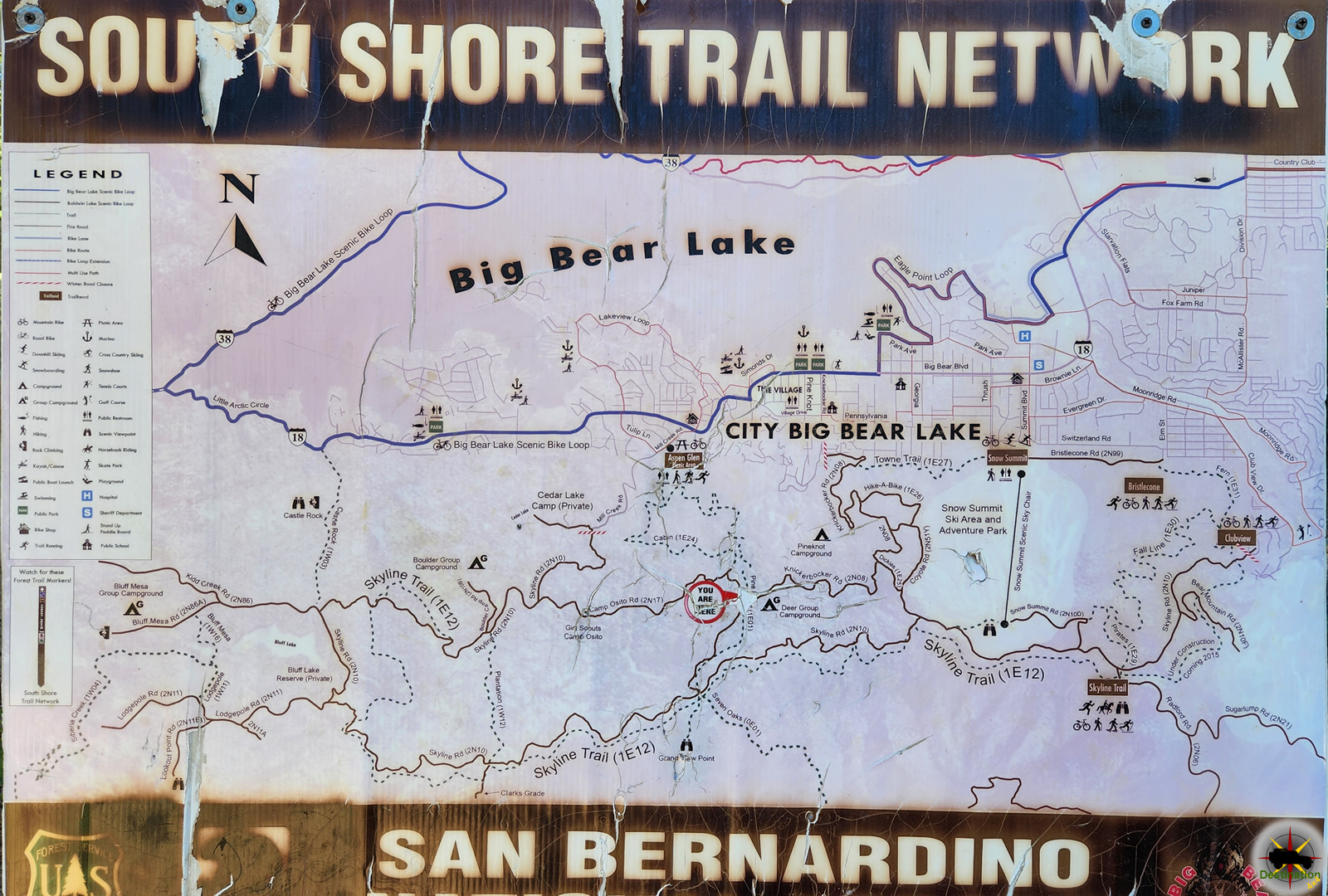

Trail Map

Camp Osito Road is part of the South Shore Trail Network located in the San Bernardino Mountains, near Big Bear, California.

Camp Osito Road – 2N17Camp Osito Road is a back country 4x4 trail which connects Knickerbocker Road to Skyline Drive in Big Bear, California. The seldom travelled road is… |

Clarks Grade 1N54Clarks Grade 1N54 Trail Head dropping down into Barton Flats from Skyline Drive. Clarks Grade 1N54 is a steep and scenic descent from the top… |

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08Knickerbocker Road - 2N08 is a steep and beautiful drive from near the town of Big Bear, California to Skyline Drive. The route is a… |

Skyline Drive 2N10Skyline Drive 2N10 offers higher elevation views of Big Bear, California Skyline Drive 2N10 is the unofficial name for USFS Road 2N10 that begins just… |

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08 is a steep and beautiful drive from near the town of Big Bear, California to Skyline Drive. The route is a popular destination and common for hikers, bikes and vehicles alike. The route winds up the mountain from the village in Big Bear up to the top of the mountain offering some spectacular vistas and the valley below.

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08 is accessed from Highway 18 in Big Bear, about two blocks east of the village. The trail head is located 3/4 of a mile from the highway off of Knickerbocker Road. The trail begins with a tight left turn and steeply gains alititude. from the valley floor on its journey up to Skyline Drive.

Along the route, you journey deep into a lush pine forest with a few seasonal streams to nourish the lush green plant life. Manzanita Bushes fill the landscape, along with a variety of seasonal wild flowers as you continue to climb to the ridge of the mountain. Don’t forget to admire the views of Big Bear lake as you make the journey.

Once the trail terminates at the Grand View Vista at Skyline drive, there is a very small parking area to relax, picnic and enjoy the alpine view of Barton Flats and valley below. From here, you can return as you came, or pick any of several trails from the South Shore Trail Network including Skyline Drive,

Knickerbocker Road Trail Summary

| Name | Knickerbocker Road – 2N08 |

| Location | Big Bear, San Bernardino County, California |

| Latitude, Longitude | 34.2162, -116.9192 |

| Length | 4 Miles |

| Elevation Gain | 890 feet |

Trail Map

Knickenbocker Road is part of the South Shore Trail Network.

Camp Osito Road – 2N17Camp Osito Road is a back country 4x4 trail which connects Knickerbocker Road to Skyline Drive in Big Bear, California. The seldom travelled road is… |

Clarks Grade 1N54Clarks Grade 1N54 Trail Head dropping down into Barton Flats from Skyline Drive. Clarks Grade 1N54 is a steep and scenic descent from the top… |

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08Knickerbocker Road - 2N08 is a steep and beautiful drive from near the town of Big Bear, California to Skyline Drive. The route is a… |

Skyline Drive 2N10Skyline Drive 2N10 offers higher elevation views of Big Bear, California Skyline Drive 2N10 is the unofficial name for USFS Road 2N10 that begins just… |

Chloride Arizona

Chloride Arizona is the oldest continuously inhabited Silver Mining town located in Mohave County, Arizona. The name derives its named from Silver Chloride (AgCl) which is found in abundance in the local Cerbet mountains.

Chloride’s modern history began in the late 19th century when prospectors, drawn by rumors of silver and other valuable minerals, began to explore the nearby hills and canyons. In 1863, a prospector named John Moss struck silver in the area, leading to a flurry of activity as more miners and settlers arrived. The first official post office was established in 1866, and Chloride was officially born.

Chloride experienced rapid growth during the late 1800s as mines produced substantial amounts of silver, lead, zinc, and other valuable minerals. The town’s population swelled. Businesses, saloons, and other establishments sprung up to cater to the needs of the growing community. At its peak, Chloride boasted a theater, several hotels, and a bustling main street.

However, like many mining towns of the era, Chloride’s prosperity was short-lived. Fluctuating metal prices, mine closures, and the depletion of easily accessible minerals led to a decline in the town’s fortunes. By the early 20th century, Chloride entered a period of decline. Much of its population began to dwindle as residents sought opportunities elsewhere.

Despite the challenges, some residents remained in Chloride, and the town managed to maintain a semblance of its former self. The 20th century saw the rise of tourism as visitors were drawn to Chloride’s picturesque desert landscapes, historical buildings, and remnants of its mining heritage. Efforts to preserve the town’s history led to the restoration of several historic structures, including the Monte Cristo Saloon. The saloon proudly claims to be Arizona’s oldest continuously operating bar.

Modern Relevance

In recent decades, Chloride has experienced a revival fueled by a mix of nostalgia, artistic expression, and a desire to escape the hustle and bustle of city life. The town has attracted a diverse group of residents, including artists, retirees, and those seeking a slower pace of life.

One of Chloride’s most unique and captivating features is the open-air Chloride Murals project. In the early 1960s by local artist Roy Purcell, this project has transformed the town into a vibrant canvas. Murals depicting scenes from Chloride’s history, Native American culture, and the American West decorate the sides of buildings and rock formations.

Chloride Arizona Town Summary

| Name | Chloride, Arizona |

| Location | Mohave County, Arizona |

| Latitude, Longitude | 35.4047, -114.1812 |

| Elevation | 4,022 ft (1,226 m) |

| GNIS | 2882 |

| Population | 229 |

| Max Population | 2000 |